Kimiko Tsukada passed away at 1:33am, April 19, 2018 in Los Angeles.

She volunteered for me when we held the one-day-screening in four-city around the world event in New York back in 2010. She got ill after moving to LA in 2014. Thank you, Kimi-chan, for being my friend. Rest in peace. Love.

つかだきみこさん、というより、きみちゃん!と呼ぶのが自然です。

4月19日午前1時33分にロスアンゼルスのホスピスで亡くなりました。ニューヨークで友達になり、2010年、世界の4都市で同日に行った上映会では、ボランティアとして手伝ってくれました。2014年にロスに引っ越してから発病。頑張って闘病していましたが、早く逝ってしまいました。心よりご冥福をお祈りします。ありがとう、きみちゃん。会えてよかったよ。

Donated a video camera to Ainu Language School

Biratori-cho village is the home to Ainu people in Hokkaido, northern part of Japan. Their language is getting extinct and UNESCO has recognized it as critically endangered.

Only few people left who know how to speak in Ainu language. Behind it, there is a sad history: the Ainu people were discriminated against by Japanese people. So, most of parents didn’t teach Ainu language to children in early 20th century, even at home, to protect them from bullying at school.

I am Japanese and don’t remember learning much about the Ainu people in school. Maybe, there was one line in a textbook that said the Ainu people live in Hokkaido or something simple like that. I didn’t learn anything about the old law issued in 1899, the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection that prohibited the traditional way of hunting and fishing, changed Ainu names to Japanese ones, and didn’t allow talking in Ainu. This law was abolished in 1997.

I first visited Biratori-cho in 2008 and have been thinking about how they can use video for themselves, especially to preserve their culture and language.

When I visited in May this year, I attended a “Kataribe, or story-telling” project. It is a gathering of locals where old people talk about their experience as the Ainu. A local Ainu language class started this project. In the classes, elders and young people learn Ainu language and traditional songs and stories. There are also classes to teach traditional culture, such as cooking and rituals. This village is very enthusiastic about preserving the Ainu culture.

In this Kataribe project, most of the speakers were over 70 years old and I noticed the staff only used an audio recorder to capture the event. At this gathering, I happened to have a video camera, so I filmed it. I thought they should keep using a video camera to capture the Kataribe project. Unfortunately, I couldn’t stay there forever.

Since I had some second-hand cameras at home that my friends donated for my projects, I decided to send one video camera along with a nice microphone and tapes, and a digital camera. And I made a video tutorial and uploaded it on Youtube, so they could learn how to use the equipment.

They were happy to get the donation and a local newspaper wrote about it.

I told them to keep filming and we could think about what to do with the footage.

Now I need to get some editing equipment so that we can make something people can watch.

That will be my next goal, so I am looking for grants to achieve it. I would be happy to hear from anyone who has any suggestions and support.

Jose Melo Chingal from Colombia visits Ainu community

Jose Melo Chingai is a leader of the Magui community, the home of Awa people in Colombia. The village is located in the Andes Mountains, and it takes a few days to get there from Bogota the capital, traveling on several buses and then on foot.

Over 20 years, his community has been affected by a civil war among guerilla, paramilitary, and government troops. Some people were killed, some were injured, and some became refugees. Jose wanted to tell the story to the world.

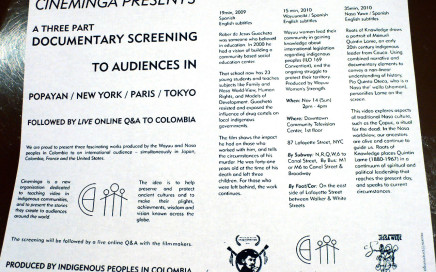

Between 2008 and 2012, I visited Colombia for a couple of times. I was working at Cineminga, a non-profit organization I founded to help indigenous people in Colombia make videos. I was teaching people how to use second-hand video equipment that I had collected, mostly from Japan, and which I gave them to keep.

A photographer friend, Daisuke Shibata, told me about Jose, and I gave him a digital camera to bring to Jose. Cineminga helped Jose create a blog page about his community by using that camera. My colleague translated it from Spanish into English, and I translated it into Japanese.

In May of 2015, Daisuke invited Jose to Japan by raising travel costs through a crowd funding campaign. Their goal is to let Japanese people know about Jose’s community and his spirit, and to ask support to create a museum in his community so in the future people can see what happened there.

Daisuke and Jose travelled all over Japan. One of the places they visited was Biratori-cho village in Hokkaido, the northern part of Japan, where the Ainu people live. I helped them by filming their visit.

Jose and the Ainu people found a lot in common: they way of living with nature, the way they cook, the crops they grown, and even the way they make handcrafted bags of very similar design. Jose was interested in seeing and learning about a local non-profit organization that has been preserving traditional plants that are important for the Ainu people. This organization asks people to buy a small piece of land and plant seeds to grow, so that in the distant future, they will have a big forest. It was nice to see people interacting and exchanging ideas.

The biggest surprise to me was that even thought this was Jose’s first trip abroad, a very long trip, and he was traveling all over Japan, he never appeared tired. Rather, he was always enthusiastic about learning new things and meeting people.

Now I am going to start editing his footage. Daisuke will brining the DVD to Jose’s village, Magui.